Relax, Everything will be Bouquet.

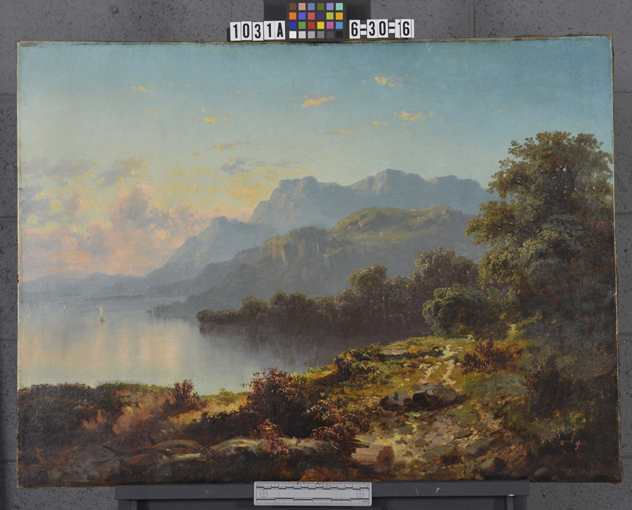

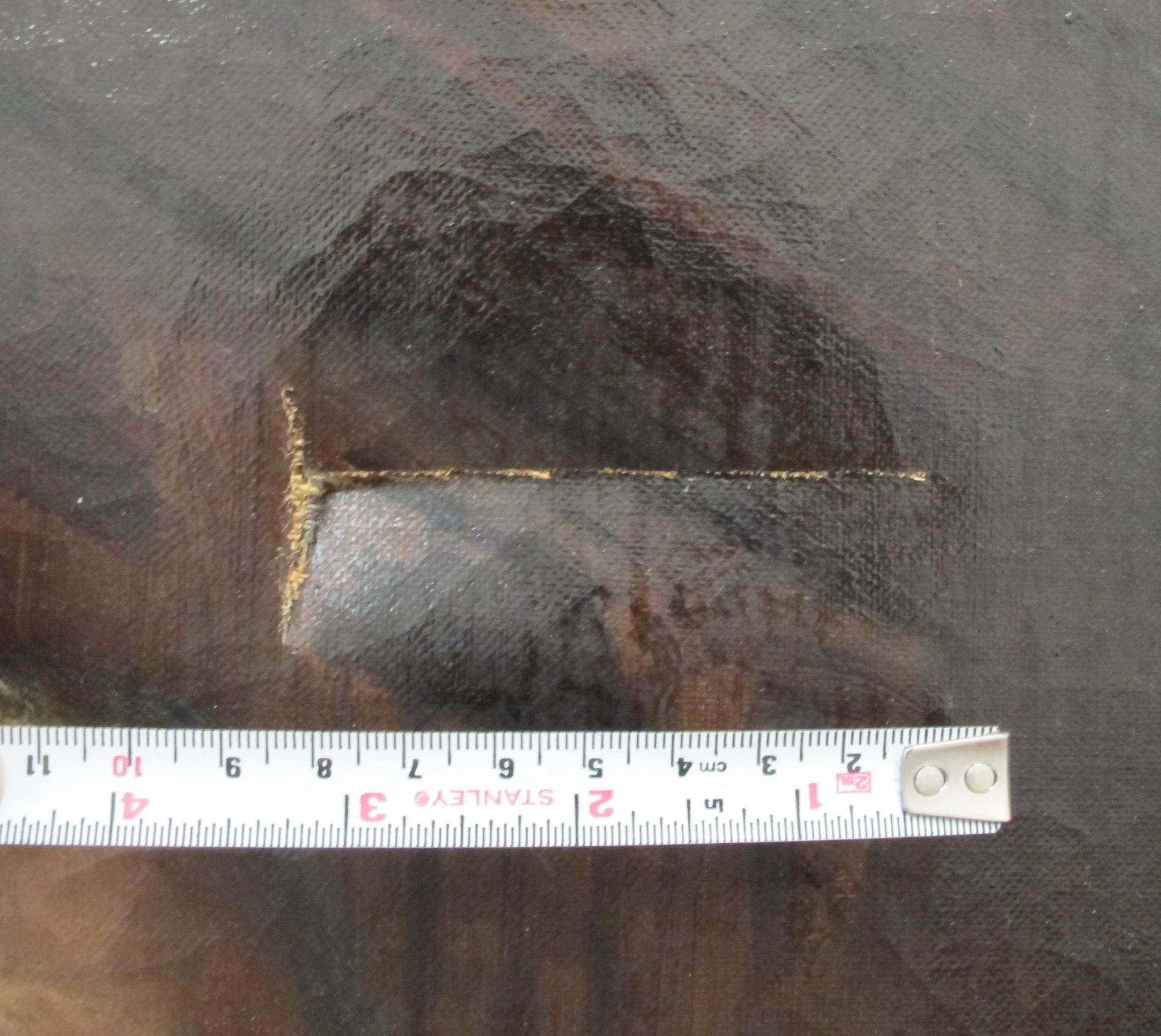

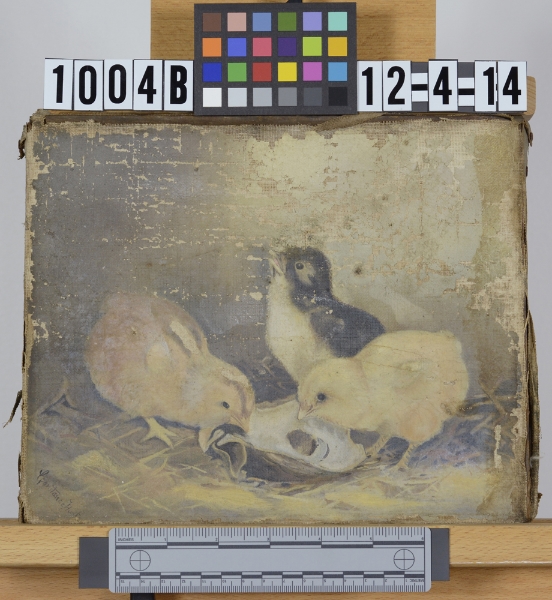

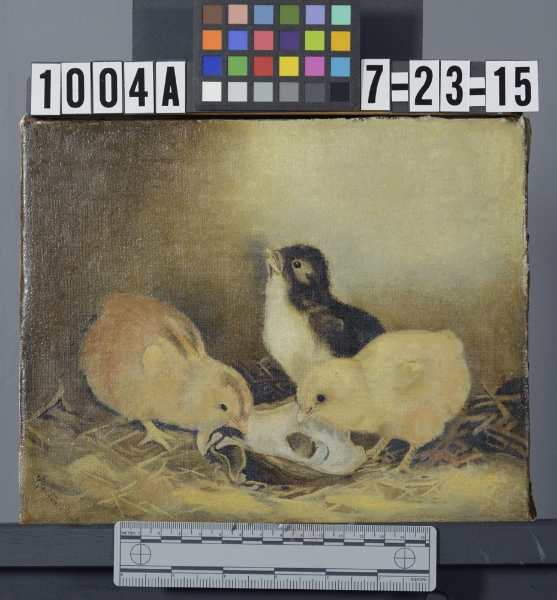

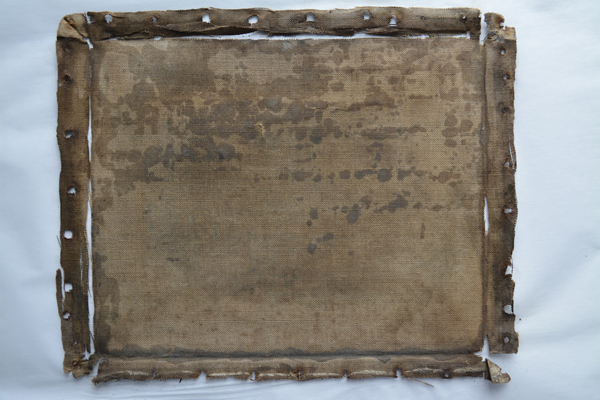

During conservation treatment, it is our practice that all structural work (work pertaining to the support) should be addressed before cleaning and other aesthetic work. This painting, Still Life by Carl Furbush, exhibited dramatic planar distortions (undulations) of its canvas support likely due to previous rolled housing prior to stretching. A raking light shot is used to document any deformations of the canvas and/or media. In this case, the light was situated along the top edge of the canvas to emphasize the strong horizontal creases and undulations.

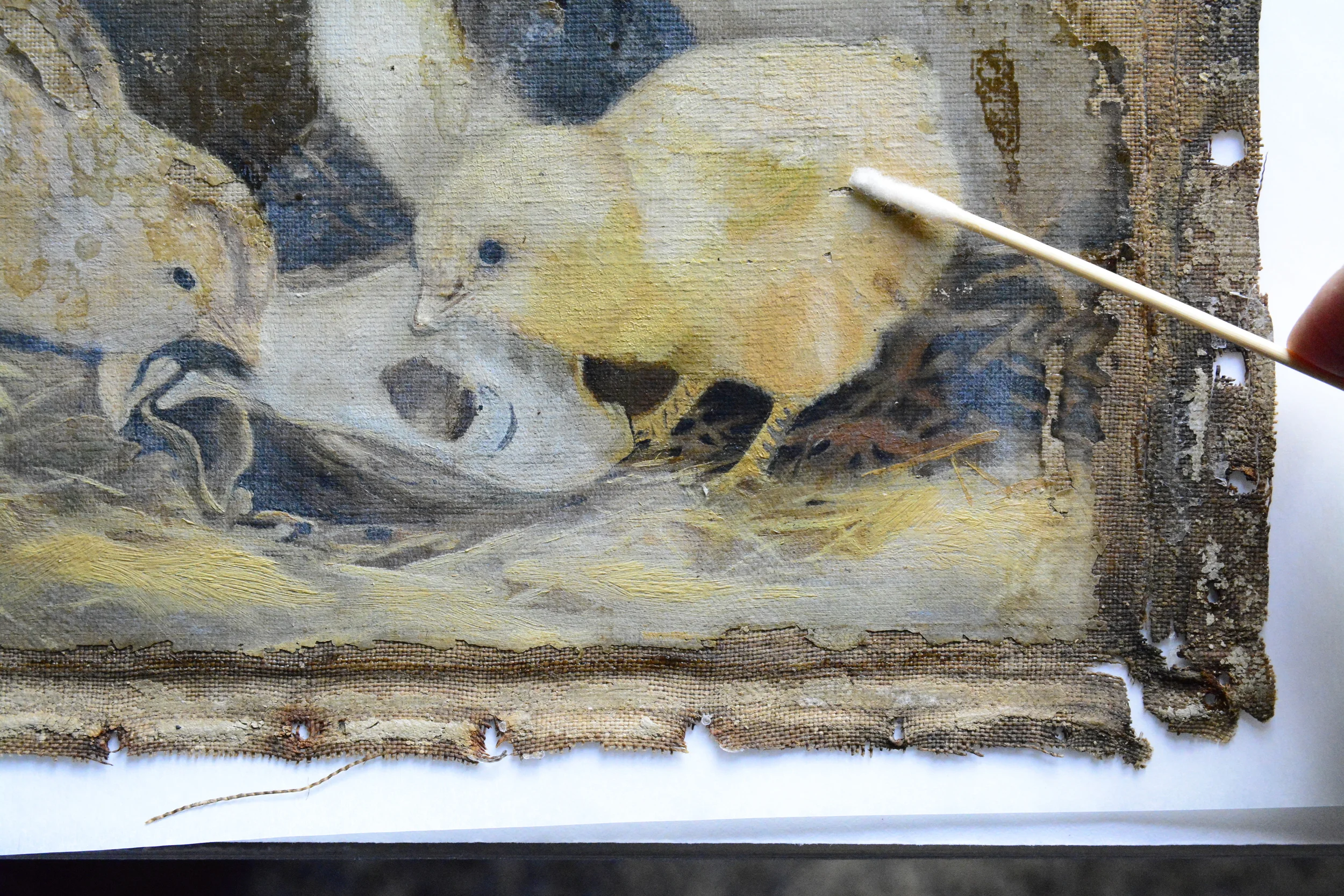

In order to relax the strong undulations of the canvas, the painting was un-stretched and was humidified on a heat/suction table to evenly relax the entire length of the canvas. Following the humidification treatment, the painting was re-stretched and the surface was cleaned of a heavy grime layer. Click on the arrows of the slideshow beneath to see the finished treatment!