The treatment of Martin B. Leisser's portrait of Benjamin Franklin

Martin B. Leisser (1845-1940) was a prominent Pittsburgh area landscape and portrait painter. Leisser was born on the South Side of Pittsburgh and began his career by painting flowers on furniture. He

later lived and trained in Munich for several years with his family.

Leisser went on to paint the likenesses of the Carnegie family, among other socialites of the Pittsburgh elite, and would be known as “the father" of the art school at Carnegie Tech. He was also the

headmaster of the former School of Design for Women.

Though better known for his Pittsburgh landscapes, his portraits employ the same attention to detail, subtle hues, and softness of hand.

One of his winter scenes was featured in this recent “Pittsburgh

Post-Gazette” article:

http://www.post-gazette.com/life/holidays/2014/12/25/Landscape-artist-captured-mood-of-Sixth-Avenue-Downtown-in-1902-Pittsburgh-snowstorm/stories/201412250027

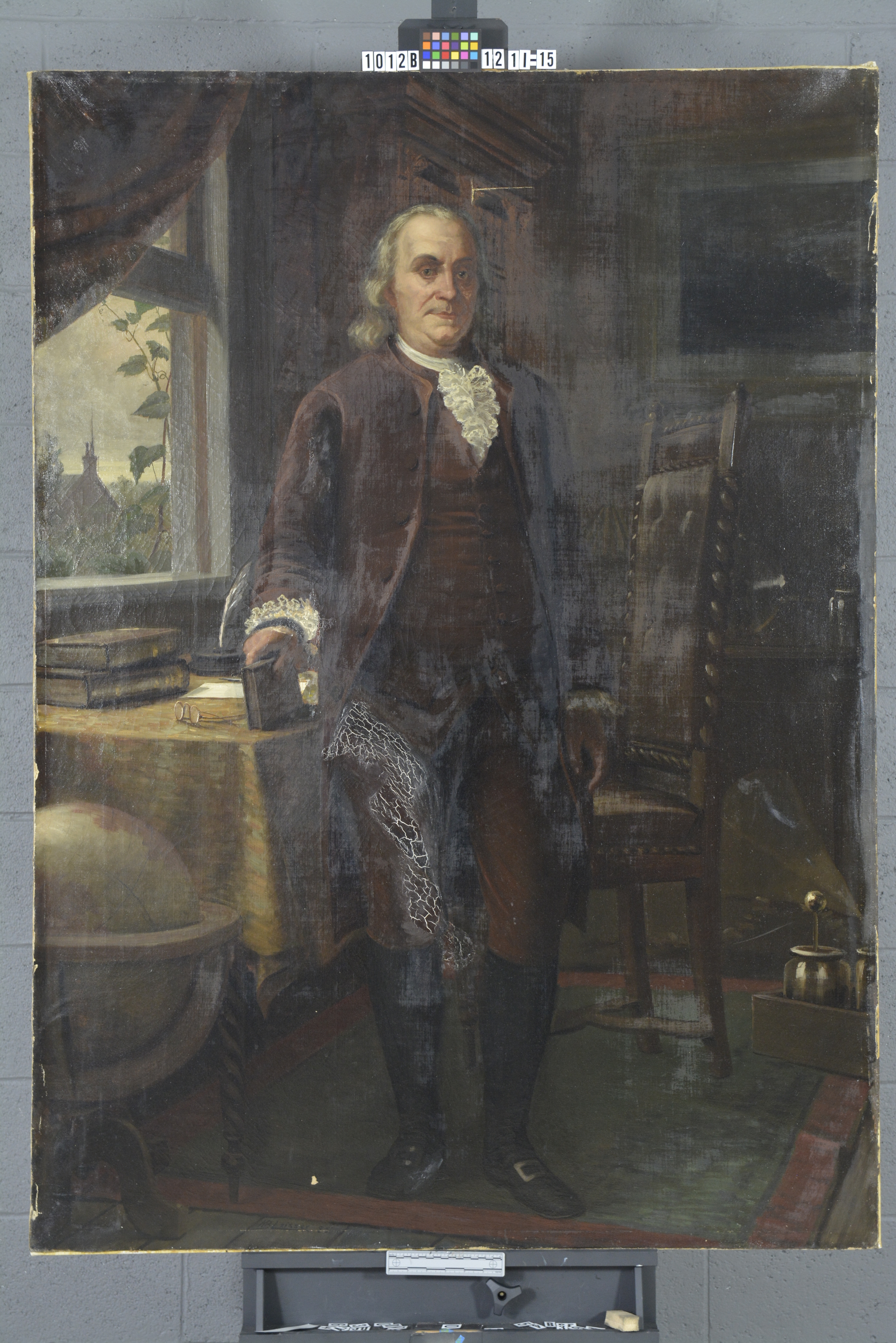

Martin B. Leisser's portrait of Benjamin Franklin is currently owned by Washington and Jefferson College in Washington, Pennsylvania, and hangs in the U. Grant Miller Library. The painting is currently being treated due to damage sustained by a fall and subsequent impact with a desk.

The damage sustained by the impact mainly consists of a four-inch tear above the subject's head. Aside from the damage, the painting has been the apparent recipient of restoration attempts, presumably by a restoration hobbyist, and was lined to a preprimed canvas. There is

also a large area of damage with cracking overpaint on the subject's thigh, in addition to excessive overpaint in scattered locations, uneven varnish, and scattered areas of flaking. In order to treat the tear above Ben's head, the old lining and restorations required removal, as the lining canvas was failing around the edges and around the area of damage.

I look forward to sharing the progress of this treatment with you. Stay tuned for updates and during-treatment photographs!